I wrote the worlds worst emulator

to reverse engineer the c64 Bubble Bobble RNG

Weirdly elegant in its own broken way.

- ChatGPT

Background

After my Bubble Bobble Wind Currents post, I was contacted by Davide Bottino, who remasters c64 arcade ports by redrawing the graphics to match the original arcade versions as closely as possible. He had just wrapped up the graphics for Toki and was looking for a new project. Bubble Bobble seemed like the ideal game.

He asked me if I was able to patch the c64 game with new graphics. I’d been meaning to update just a few sprites since I saw a post by Cal Skuthorpe years ago, so I was all for it. While I initially didn’t personally care much about Davide’s arcade-perfect vision, I did respect it and felt it was worthwhile.

Getting new player/enemy sprites and level graphics into the game was simple enough. I built a tool for him to use so he could iterate on the designs on his own. Pretty soon, Davide had replaced them all with his excellent art. But he had some minor complaints. Like the colors of the sprites that couldn’t be changed. It didn’t take much to convince me to add more features to the tool.

Some of the game sprites were much harder to patch. Specifically the large bonus watermelon. It uses 2x2 hardware sprites. Other multi-sprites like this are laid out sequentially in memory, left-to-right, top-to-bottom. But when I first tried to extract the watermelon graphics, the top 2 sprites were just noise.

I ran the game in Retro Debugger to find out how the game reads the watermelon sprites. It turns out the noise pixels are indeed copied over to the sprite memory region, so I believe all 4 sprites were initially used for graphics. But since the 2 top sprites are mostly empty, presumably Steve Ruddy used them when he ran out of space elsewhere. After copying the noise pixels, separate code blanks them out again and copies the remaining sprite data from 2 other, unrelated locations.

There are several instances like this, where modifying graphics required deep-diving into the code to reverse engineer exactly how it works in order not to break anything. It looks like the old sprite region now contains code, so overwriting it would most likely crash the game.

Powerups

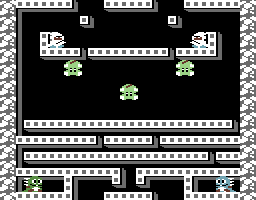

Davide and I both love this type of code archeology. Especially where it relates to the game logic. Bubble Bobble on the c64 spawns 2 special items on each level; one bonus points item, and one powerup. They have a fixed location per level, and are spawned after a random time. One thing we were curious about was why certain powerups often show up on specific levels. On level 1, there’s usually a shoe, on level 5 a “flaming skull”, and on level 6 a purple umbrella. Is there a simple formula? Or is the random number generator just poorly implemented?

Turns out it’s both, kind of.

The Random Number Generator

While looking through the code responsible for the powerups, I came across a function that was often used to generate a value to index into some array. Just the kind of thing you would use a random number for.

E9EA A5 26 rng LDA $26

E9EC 0A ASL A

E9ED 26 27 ROL $27

E9EF 26 26 ROL $26

E9F1 A5 27 LDA $27

E9F3 45 26 EOR $26

E9F5 65 27 ADC $27

E9F7 4D 06 DC EOR $DC06

E9FA 85 26 STA $26

E9FC 60 RTS

It looked a lot like a Linear Feedback Shift Register, something I remember reading about on forums in the early 2ks. Probably on GameDev.net, Flipcode or cfxweb.net. Good times.

LFSRs are fast and give perfect uniform distribution, but they’re notoriously bad as general-purpose RNGs. Especially when not given a good source of entropy as seed values. That lined up well with the behavior I was seeing.

In old machines like the c64 or the NES where there’s no clock, the entropy usually comes from player input, and that’s how Bubble Bobble does it too. At the player select screen, the RNG is called every frame, but the value is discarded. The random seed coming into level 1 after starting the game therefore depends only on the exact frame where you press “1” for single player etc.

But I imagine most players would get used to this screen, and hit the key pretty quickly and consistently, perhaps in 0.3 to 0.5 seconds. That’s just a 0.2 second span. With 50 (pal) frames per second, that’s only 10 possible initial random seeds. Maybe this was the reason for the shoe on level 1?

Powerup Selection

I tried investigating the powerup selection code more closely, but bit twiddling and convoluted branching made it hard to follow.

For example, the RNG is in one place used to index into a 32 element array segment, so you’d expect the code to mask the result with 0x1f. But instead, it used 0x1e. Care to guess why?

093F 20 EA E9 JSR rng

0942 29 1E AND #$1E

0944 69 0A ADC #$0A

0946 85 58 STA $58

The masking is followed by an addition. Adding on the 6502 processor takes the carry-bit into account, so if it isn’t wanted, an extra “clear carry”-instruction must be added first. The RNG implementation just happens to place one random bit in the carry flag, so instead of explicitly clearing the carry bit, the mask clears the corresponding bit in the random number.

Examining all the code in detail like this would take me weeks. If I could instead run the logic for selecting the powerup with all possible input values, I wouldn’t need to understand it, I could just count the probabilities.

The Emulator

I first tried porting the 6502 asm to typescript line by line, but I couldn’t really tell what each line was meant to achieve anyway, so that didn’t help me a lot.

The more fun option was to emulate the original code, but I wanted to only run the powerup selection, not the entire game. There are command line emulators available for this kind of use case, but setting one up and figuring it out felt daunting. Especially since they seem to be mostly written in C and take binary 6502 machine code as input. I would at the very minimum have to compile the powerup code to a separate binary and somehow instrument it, possibly by hacking the emulator too. I just didn’t want to deal with any of that.

So instead, I hacked together my own minimal emulator in typescript.

type State = {

regs: {

A: number;

X: number;

Y: number;

};

zp: {

"04": number;

"26": number;

"27": number;

"58": number;

};

flags: {

carry: boolean;

zero: boolean;

negative: boolean;

};

};

export function adc(state: State, value: number): void {

state.regs.A += value + (state.flags.carry ? 1 : 0);

state.flags.zero = state.regs.A === 0;

state.flags.carry = !!(state.regs.A & 0x100);

state.regs.A &= 0xff;

state.flags.negative = !!(state.regs.A & 0x80);

}

test("adc", () => {

const state = createState();

state.regs.A = 1;

adc(state, 1);

expect(state.regs.A).toStrictEqual(2);

});

// etc.

The code only ever touches those 4 zeropage addresses, so I only support them. Same thing with the flags. Unit testing each aspect of the instructions as described at 6502.org was super helpful. Thanks, “obelisk”!

It is not quite as stupid as it sounds. I wasn’t trying to emulate an entire 6502 computer, only enough of it to run the RNG and some glue code. I skipped all branching, opting instead to implement it as normal if-statements, loops and function calls in typescript. That way, I didn’t even need a program counter or instruction addresses.

All I needed was a handful of instructions, each implemented as a separate typescript function, manipulating a state of a ram, registers and processor flags. The result was basically a source port/emulator hybrid.

With the emulator working, the RNG function becomes:

function rng(state: State) {

// e9ea lda 26

ldaZp(state, "26");

// e9ec asl

asl(state);

// e9ed rol 27

rolZp(state, "27");

// e9ef rol 26

rolZp(state, "26");

// e9f1 lda 27

ldaZp(state, "27");

// e9f3 eor 26

eorZp(state, "26");

// e9f5 adc 27

adcZp(state, "27");

// e9f7 eor dc06

const dc06 = 0xff;

eorAbs(state, dc06);

// e9fa sta 26

staZp(state, "26");

// e9fc rts

}

The code to select the powerup is:

2BFC A6 26 L2BFC LDX $26

2BFE A4 27 LDY $27

2C00 A5 10 LDA $10

2C02 85 26 STA $26

2C04 85 27 STA $27

2C06 20 EA E9 JSR rng

2C09 18 CLC

2C0A 69 01 ADC #$01

2C0C 29 1F L2C0C AND #$1F

2C0E 86 26 STX $26

2C10 84 27 STY $27

2C12 85 04 STA $04

2C14 20 EA E9 JSR rng

2C17 29 0F AND #$0F

2C19 D0 09 BNE L2C24

2C1B 20 EA E9 JSR rng

2C1E 29 01 AND #$01

2C20 09 1E ORA #$1E

2C22 D0 0E BNE L2C32

2C24 C9 07 L2C24 CMP #$07

2C26 90 05 BCC L2C2D

2C28 A5 04 LDA $04

2C2A 4C 32 2C JMP L2C32

2C2D 20 EA E9 L2C2D JSR rng

2C30 29 1F AND #$1F

It leaves the selected powerup index in the A register, and in typescript that becomes:

export function getRandomPowerupForLevel(

state: State,

levelIndex: number

): number {

// 2bfc ldx 26

ldxZp(state, "26");

// 2bfe ldy 27

ldyZp(state, "27");

// 2c00 lda 10

// zp10 is the level index.

lda(state, levelIndex);

// 2c02 sta 26

staZp(state, "26");

// 2c04 sta 27

staZp(state, "27");

// 2c06 jsr e9ea

_e9ea(state);

// 2c09 clc

state.flags.carry = false;

// 2c0a adc #01

adc(state, 0x01);

// 2c0c and #1f

and(state, 0x1f);

// 2c0e stx 26

stxZp(state, "26");

// 2c10 sty 27

styZp(state, "27");

// 2c12 sta 04

staZp(state, "04");

// 2c14 jsr e9ea

_e9ea(state);

// 2c17 and #0f

and(state, 0x0f);

// 2c19 bne 2c24

if (state.flags.zero) {

// 1/16 chance to get here due to 2c17, 2c19.

// 2c1b jsr e9ea

_e9ea(state);

// Only keep the lowest bit.

// 2c1e and #01

and(state, 0x01);

// 2c20 ora #1e

ora(state, 0x1e);

// 2c22 bne 2c32

if (!state.flags.zero) {

// Can zero ever happen?

return;

}

}

// 2c24 cmp #07

cmp(state, 0x07);

// 2c26 bcc 2c2d

if (state.flags.carry) {

// 2c28 lda 04

ldaZp(state, "04");

// 2c2a jmp 2c32

return;

}

// 2c2d jsr e9ea

_e9ea(state);

// 2c30 and #1f

// There are 32 normal powerup items + 3 special. 0x1f == dec31

and(state, 0x1f);

return state.regs.A;

}

Results

I ran the powerup selection logic using all 65k possible 16-bit RNG seeds and calculated the average probabilities of each powerup on all 100 levels. I dumped the results into a spreadsheet and sent it to Davide.

Dominant Powerups

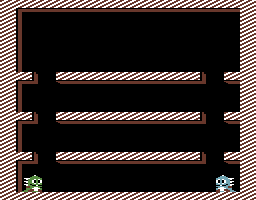

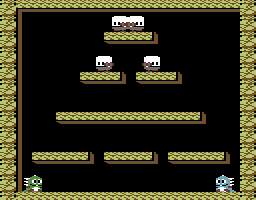

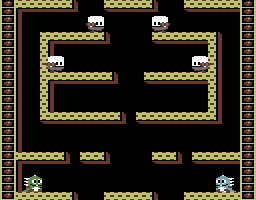

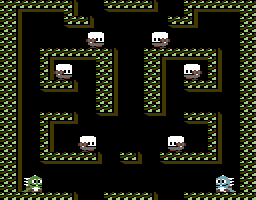

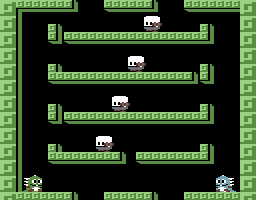

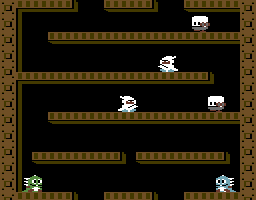

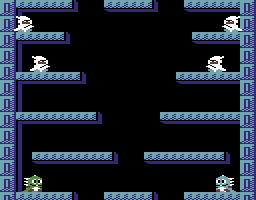

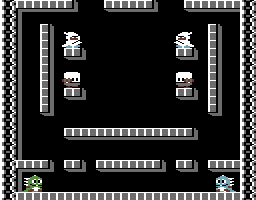

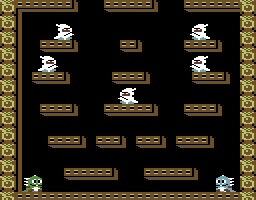

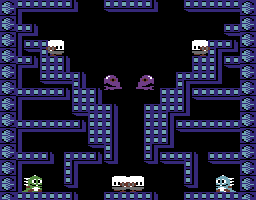

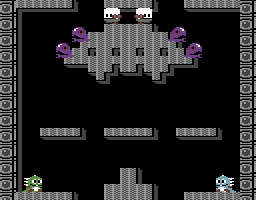

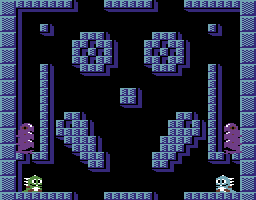

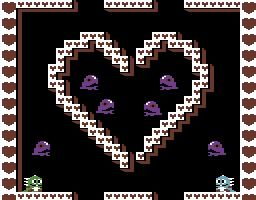

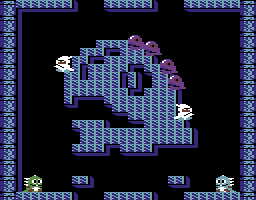

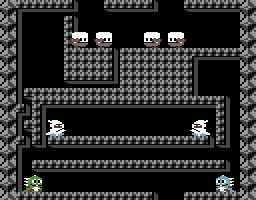

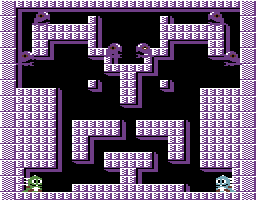

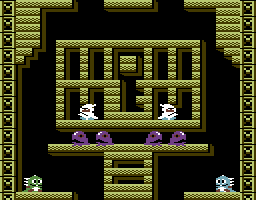

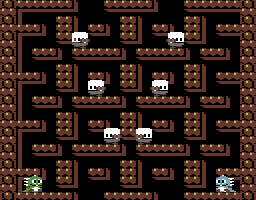

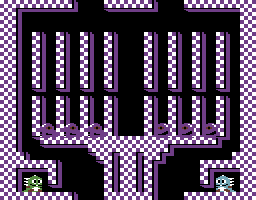

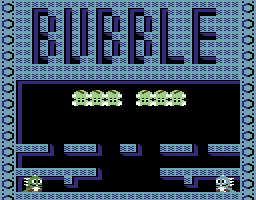

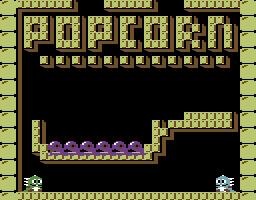

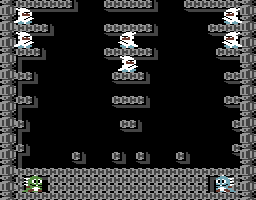

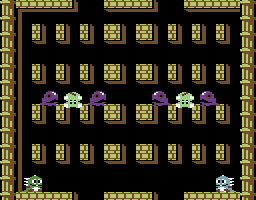

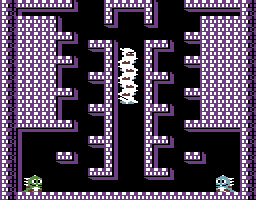

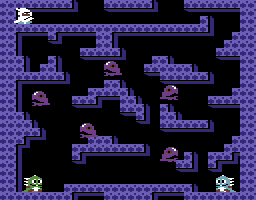

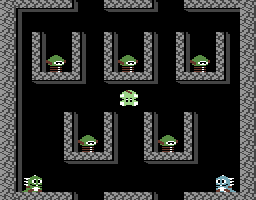

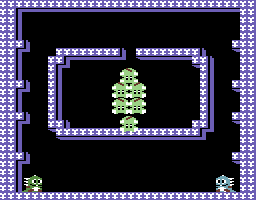

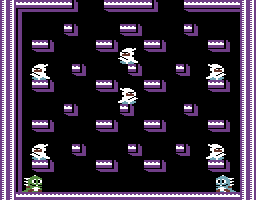

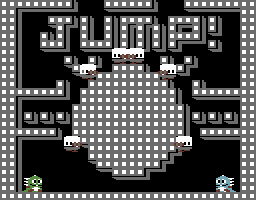

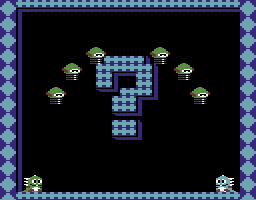

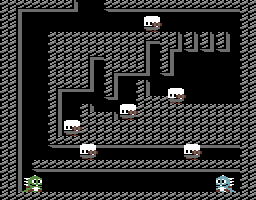

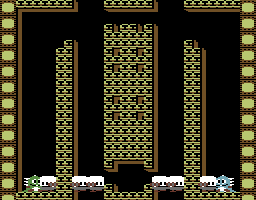

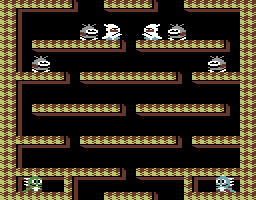

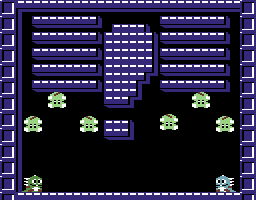

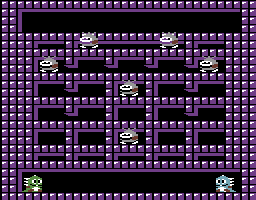

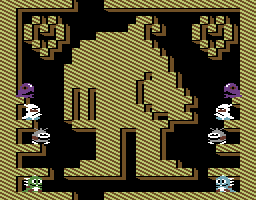

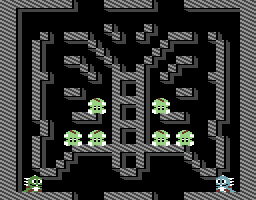

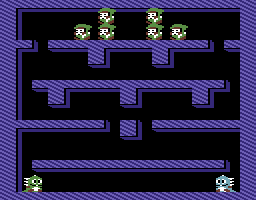

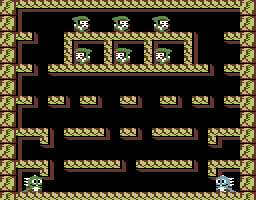

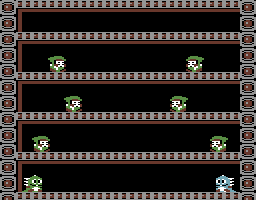

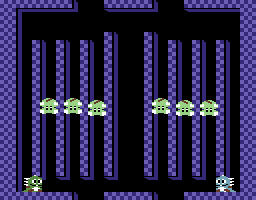

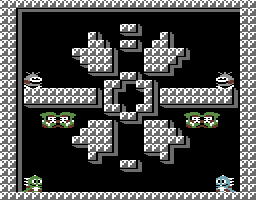

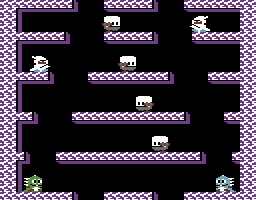

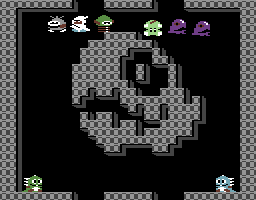

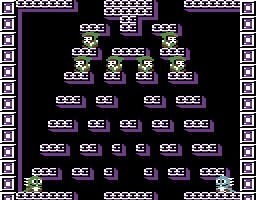

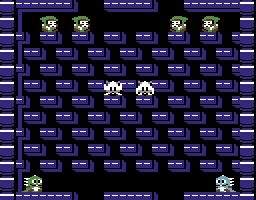

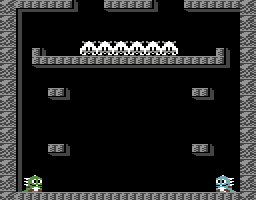

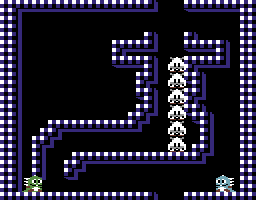

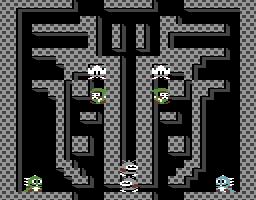

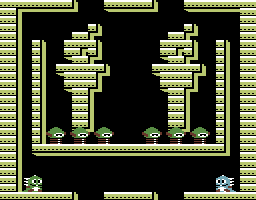

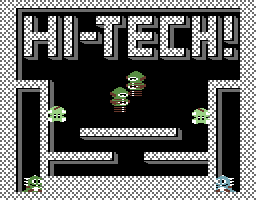

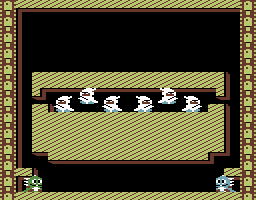

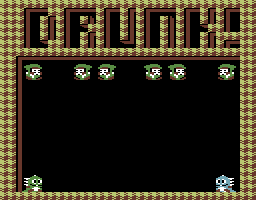

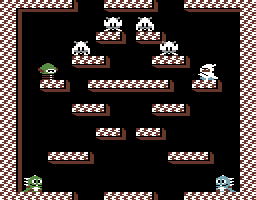

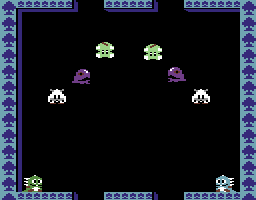

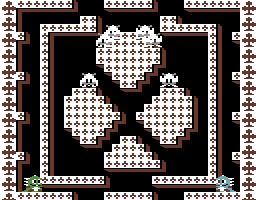

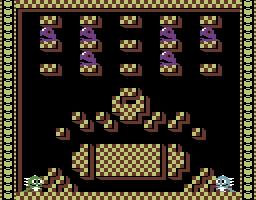

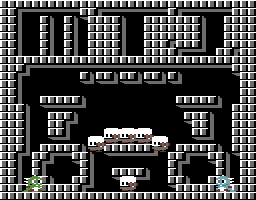

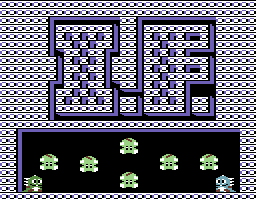

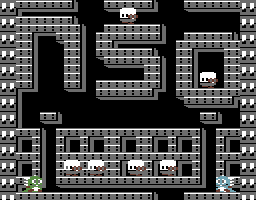

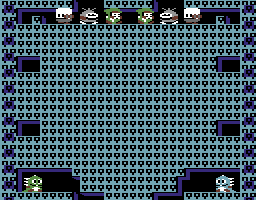

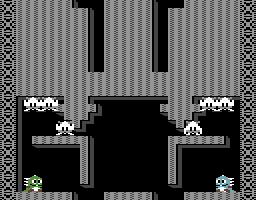

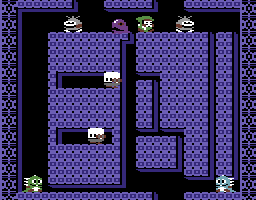

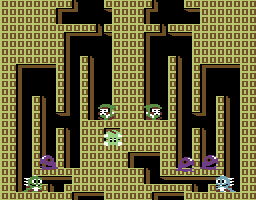

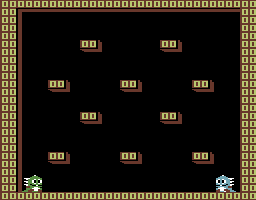

We were excited to see that each level has a single dominant powerup, appearing with about 50% probability. Looking at images of the levels felt strange, since I somehow knew that their dominant powerup was correct, even though I hadn’t consciously noticed before.

Davide noticed the pattern before I did: only even-numbered powerups were ever dominant, and their index simply decremented by two each level. Expressed in typescript:

function getDominantPowerup(levelIndex: number): number {

return (-levelIndex * 2) & 0x1f;

}

Starting with powerup index 31 on level index 0, it is decremented by 2 for each successive level, wrapping around at 0.

This means only half of the 32 powerups are ever used as the dominant one. The remaining 16 powerups are only available from the 50% non-dominant random spawns.

The reason was straightforward. The level number was used directly as the seed for the RNG.

That ties the powerup to the level, which makes sense from a game design perspective. Using the RNG was probably meant to mix up the powerups, since similar items like candies and bottles are stored sequentially in memory.

The restriction to only even indices seems like a happy accident, not a deliberate decision. With half of the powerups being so much more rare, it feels so much more rewarding to finally get them. Or perhaps it wasn’t noticed at all.

Random Powerups

In the 50 % of the cases when the dominant powerup doesn’t spawn, the remaining 50 % probability is distributed roughly evenly among the 32 powerups. But not quite. The shoe, the white staff and red staff never spawn as random powerups. And since the white staff has an odd index, it never spawns as a dominant powerup either. There could well be some other mechanism to spawn powerups that I haven’t discovered, but if not, the white staff is never spawned at all.

You can force it to spawn on every level though. Enter this in the Vice monitor:

> 2c26 ea

> 2c27 ea

> 2c28 a9

> 2c29 01

May not work in some cracked versions of the game.

| Item | Probability |

|---|---|

| shoe | 0.00 % |

| white staff | 0.00 % |

| red staff | 0.00 % |

| yellow candy | 0.39 % |

| purple candy | 1.18 % |

| blue candy | 0.39 % |

| red cross | 0.39 % |

| yellow cross | 1.57 % |

| blue cross | 1.96 % |

| red lamp | 2.35 % |

| yellow lamp | 1.18 % |

| purple lamp | 2.75 % |

| purple ring | 4.31 % |

| red ring | 2.35 % |

| blue ring | 3.53 % |

| clock | 3.14 % |

| green potion | 1.96 % |

| purple potion | 0.78 % |

| yellow potion | 3.14 % |

| green crystal ball | 1.57 % |

| blue umbrella | 2.35 % |

| yellow staff | 2.75 % |

| purple umbrella | 0.39 % |

| blue staff | 1.96 % |

| power heart | 2.35 % |

| yellow box | 0.78 % |

| blue box | 1.57 % |

| white box | 0.78 % |

| green lamp | 0.39 % |

| bomb | 0.78 % |

| purple crystal ball | 3.92 % |

| bell | 1.96 % |